Could a book with wooden covers and bound together with string and brown paper actually be the future shape of how we digest literature in the digital age? A new project involving Neil Gaiman and Nick Harkaway suggests it might.

If you live in Bristol, you might already be a participant in the These Pages Fall Like Ash project, which until May 8 will be attempting to reconcile any perceived war between physical literature and e-books in a rather startling way.

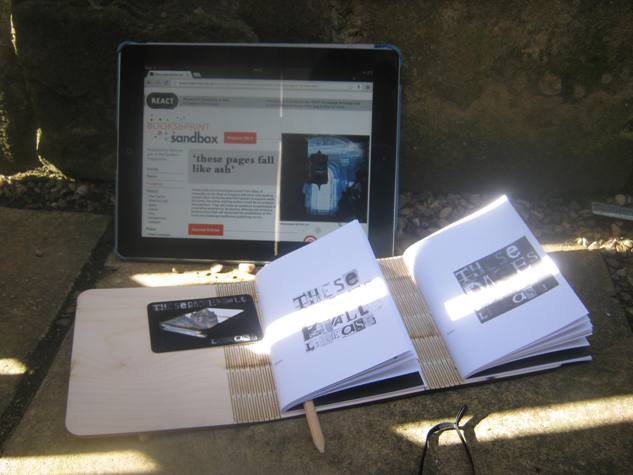

Conceived by Bristol-based writer Tom Abba along with the artists’ collective Circumstance, These Pages Fall Like Ash is a story of two cities which overlap in space and time but are either unaware of or try to ignore each other—just as, for some, the twain worlds of digital literature and physical books are things that shall never meet.

Abba has brought on board two major talents to help tell the story— Nick Harkaway, the author of The Gone-Away World and Angelmaker, and Neil Gaiman, whose The Ocean at the End of the Lane will be published this June.

During his recent keynote speech at the Digital Minds Conference at the London Book Fair, in which he urged publishers and readers to be bold in the brave new world of books that is ahead, Gaiman touched on These Pages Fall Like Ash as a prime example of embracing change.

He said: “These Pages Fall Like Ash…is going to be a story that’s told across two books—one of which is going to be a beautiful little handmade wooden book with information and where you can also write stuff yourself, and the other is going to be a digital text hidden on hard drives all across the city, in this case Bristol, and read on a mobile device, the idea being to create two books together in a singular reading experience. We’ve created a story about a moment in which two cities overlap, existing in the same space and time, but unaware of each other until now. And people finding this stuff on their mobile devices are going to become part of the story. And again, it’s that thing where you’re creating something that would literally have been unimaginable, we didn’t have the tools or the technology to imagine.”

The Bristol project started on Saturday April 20 and runs for two-and-a-half weeks. Abba says: “I want us all to see our city through new eyes—to learn things about the places we walk we were never aware of. These Pages Fall Like Ash is an exciting new reading experience that will invite people to not only explore all of these elements and more, but to become part of the narrative itself. I can’t wait to see what the participants bring to its story and what the final page will reveal.”

The book has two distinct sets of pages, designed to be annotated and customised by the user to create a unique volume for everyone who takes part. The first batch of pages details a shadowy city called Portus Abonae which occupies the same space as “our” Bristol. The second set of pages, facing the first, details the more concrete locations and stories of the “real world”. But just as the fictional city overlaps with the real one, so do the pages interleave with each other, like a deck of cards being shuffled. As participants pass through various areas of Bristol they activate hidden extra content stored locally on computers in the vicinity.

It seems a beautiful, almost otherworldly idea, and while These Pages Fall Like Ash is a specifically localised event, there seems no reason why the principles behind it could not be widened out on a global scale if needs be. As well as reconciling digital and physical, the project also makes the book something to be desired and held, a wonderfully tactile and immersive experience. With its covers of wood, These Pages Fall Like Ash is a “dead tree” book in its most literal evocation, but with the invisible heft of the whole internet ocean behind it.

Or, as Gaiman also said in his Digital Minds speech: “I suspect that one of the things that we should definitely be doing in digital in the world of publishing is making books—physical books—that are prettier, finer, and better. That we should be fetishizing objects. We should be giving people a reason to buy objects, not just content, if we want to sell them objects. Or we can just as easily return to the idea that one does not judge a book by its cover.”

David Barnett is an author and journalist based in the north of England. His novel Gideon Smith and the Mechanical Girl, the first in a steampunk/alternate history/Victoriana series, is published in September 2013 by Tor Books.